There’s a moment in Hayao Miyazaki’s film My Neighbor Totoro that’s stuck with me since I first watched it a decade ago. Satsuki Kusakabe is searching for her missing sister, Mei. Looking for help, she sprints towards the huge camphor tree where the magical creature Totoro lives. She pauses for a moment at the entrance to a Shinto shrine that houses Totoro’s tree, as if considering praying there for Totoro’s help. But then she runs back to her house and finds her way to Totoro’s abode through the tunnel of bushes where Mei first encountered him. Totoro summons the Catbus, which whisks Satsuki away to where Mei is sitting, beside a lonely country road lined with small statues of Jizo, the patron bodhisattva of children.

It’s Satsuki’s hesitation in front of the shrine’s entrance that sticks with me, and what it says about the nature of spirits and religion in the film. We don’t really think of the movies of Hayao Miyazaki as religious or even spiritual, despite their abundant magic, but some of his most famous works are full of Shinto and Buddhist iconography—like those Jizo statues, or the sacred Shimenawa ropes shown tied around Totoro’s tree and marking off the river god’s bath in Spirited Away. Miyazaki is no evangelist: the gods and spirits in his movies don’t follow or abide by the rituals of religion. But the relationship between humans and gods remains paramount.

Miyazaki’s gods and spirits aren’t explicitly based on any recognizable Japanese “kami” (a word that designates a range of supernatural beings, from the sun goddess Amaterasu to the minor spirits of sacred rocks and trees). In fact, whether Totoro is a Shinto spirit or not is a mystery. He lives in a sacred tree on the grounds of a Shinto shrine. The girls’ father even takes them there to thank Totoro for watching over Mei early in the film. But Satsuki calls Totoro an “obake,” a word usually translated as “ghost” or “monster.” Miyazaki himself has insisted that Totoro is a woodland creature who eats acorns. Is he a Shinto spirit? A monster? An animal? A figment of the girls’ imaginations? The film—delightfully—not only doesn’t answer the question, it doesn’t particularly care to even ask it.

It’s a refreshing contrast to many American children’s movies, where bringing skeptical adults around to believing in some supernatural entity is often the hinge of the plot. The adults in Miyazaki’s movies either know the spirits are real (Princess Mononoke) or don’t question their children when they tell them fantastical stories (Totoro and Ponyo). The only adults who express doubts are Chihiro’s parents in Spirited Away, and they get turned into pigs. Believe in the spirits or not; they abide.

A lot of them abide in, or at least patronize, Yubaba’s bathhouse in Spirited Away. Many of the kami that appear in Spirited Away are wonderfully strange, like huge chicks and a giant radish spirit. But a few resemble traditional Japanese gods, like Haku and the “stink spirit,” who are both river dragons (unlike their fiery Western counterparts, Japanese dragons are typically associated with water). Both have been deeply injured by humans: Haku’s river has been filled in and paved over to make way for apartment buildings; the “stink spirit” is polluted with human garbage and waste, from a fishing line to an old bicycle. The gods seem more vulnerable to the whims of humans than the other way around. No wonder Lin and the other bathhouse workers are so terrified of Chihiro when they discover she’s human.

The tension between humans and spirits escalates into full-out war in Princess Mononoke, in which Lady Eboshi battles against the gods of the forest so that she can expand her iron-mining operation. Mononoke’s kami are woodland creatures: wolves, wild boars, and deer. They’re just as fuzzy as Totoro, but a lot less cuddly. Like the wilderness itself, they are elemental, powerful, dangerous, and sources of life and death. But they are also vulnerable. Mankind’s pollution and violence can corrupt nature and the spirits—one of Eboshi’s bullets turns a wild boar-god into a rampaging demon—but that damage rebounds back on mankind, particularly affecting the most vulnerable among us (much the same way poor nations and communities are currently bearing the brunt of climate change). It’s not Eboshi who ends up cursed by the boar-demon, after all; it’s Ashitaka, a member of the indigenous Emishi people. And when Eboshi manages to kill the Great Forest Spirit with her gun at the film’s climax, it sends a literal flood of death over the entire landscape.

Miyazaki doesn’t paint in black and white, though. Lady Eboshi may be a god-killer, but she’s also enormously sympathetic and even admirable. She’s a woman who’s carved out a seat of power in feudal Japan, and she uses that power to give shelter and jobs to marginalized members of society, including lepers, prostitutes, and Ashitaka himself. If deforestation and industrialization put mankind in conflict with the environment and even the gods, it can also be the only opportunity for the poor and outcast to survive. The only real villains in Mononoke are the local samurai—portrayed as violent goons—and Jikobo, a Buddhist monk in the Emperor’s service looking to collect the Great Forest Spirit’s head. The Emperor wants the godhead because possessing it will supposedly grant immortality.

The unnamed Emperor’s desire for a god’s severed head is a perversion of Japanese religious ritual. Rather than making offerings to them and beseeching the gods for favor for his people, this fictional Emperor wants to murder a god to gain eternal life for himself. It’s a small but fairly radical plot point, given that in the era the film takes place, the Emperor was himself considered a kami and a direct descendant of the sun goddess. Miyazaki isn’t indicting the Chrysanthemum Throne, though, but rather the selfish lust for personal gain by the powerful. Gods can be corrupted into curse-bearing demons, and so can those—like the monk Jikobo and the Emperor—who are supposed to serve as their intermediaries.

But while the relationships between kami and humans can be fraught and even lethal, they can also be intimate and positive. Satsuki and Mei give Totoro an umbrella and he gives them a bundle of seeds. The wolf goddess Moro raises San as her own child, and when she grows up, San fights for the forest against Eboshi. Haku rescues toddler-Chihiro from drowning, and she in turn risks her life to save his and free him from Yubaba’s service.

That intimacy is most apparent in Ponyo, about the love between a little boy named Sosuke and a goldfish who turns herself into a girl thanks to a drop of Sosuke’s blood and some powerful magical potions. While set in Japan like Totoro, Spirited Away, and Princess Mononoke, Ponyo’s supernatural world is a mythological melange. Ponyo is based on Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, but it also echoes the Japanese folktale of Urashima Taro, about a young fisherman who rescues a sea turtle and is rewarded with a visit to the undersea palace of the kami Otohime. Ponyo’s birth name is Brunhilde, a nod to the Valkyrie daughter of Wotan in the Germanic Nibelungenlied. And her mother is Gran Mamare, a sea goddess with a Latinish name, but who one Japanese sailor calls Kannon, the Buddhist goddess of mercy. More than anything, she seems to be the ocean itself, ancient and immeasurably powerful. Our religious myths and folktales, Ponyo suggests, are mere approximations for the true nature of the earth and its spirits.

In all Miyazaki’s movies, it’s children who best grasp that nature. Sosuke and Ponyo love each other; so do Chihiro and Haku. No adult ever even sees Totoro or the Catbus, though they may feel their presence in the lilt of strange music on the air or a gust of wind (this may even extend to viewers; I’d seen Totoro countless times, but it was my 3-year-old son Liam who pointed out to me that the gust of wind that blows the firewood out of Satsuki’s hands near the beginning of the film is likely the invisible Catbus running by).

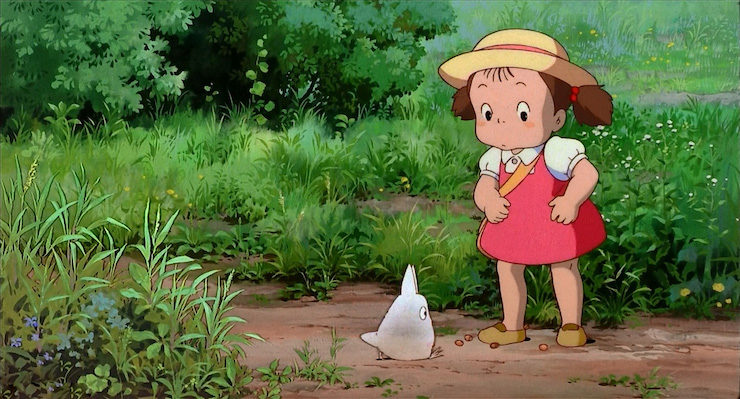

It’s not that children are pure and innocent and unquestioning—Miyazaki’s young protagonists are thoroughly human and flawed. It’s that they’re open to the spirits in ways adults are not. They don’t mediate their experience of nature and the world through the rituals of religion or calcified worldviews. Mr. Kusakabe may need to visit the camphor tree shrine to speak to Totoro, but Satsuki and Mei don’t—they can find their way to him from their own yard. Adults see what they expect to see. Children have few expectations for what is and isn’t lurking out there in the world; they’re the ones who glimpse shadows moving in the gloom of an abandoned amusement park, a goldfish returned in the shape of a girl, or a small white spirit walking through the grass.

Miyazaki’s films don’t invite us to any particular faith or even belief in the supernatural, but they do invite us to see the unexpected, and to respect the spirits of trees and woods, rivers and seas. Like Totoro and Gran Mamare, their true nature and reasoning are beyond our comprehension. Call them kami, or gods, or spirits, or woodland creatures, or Mother Nature, or the environment. They are there if we know where to look, and their gifts for us are ready if we know how to ask. We have only to approach them as a child would—like Satsuki, Mei, Chihiro, and Sosuke—with open eyes and open hearts.

Austin Gilkeson formerly served as The Toast‘s Tolkien Correspondent, and his writing has also appeared at Catapult and Cast of Wonders. He lives outside Chicago with his wife and son.